Emergency Medicine isn’t sold on TPA for stroke: Stroke drug side effects limit use.

Stroke drug side effects limit use

Ann Arbor, MI, May. 2 (UPI) — The only drug approved to treat stroke victims is not used by all U.S. emergency physicians because of concerns about side-effects, a Michigan study found.

The drug, called rt-PA, carries a 6.4 percent risk of a brain hemorrhage in stroke victims, a concern that causes about a quarter of emergency room physicians to avoid using it, according to University of Michigan Health System researchers.

The study, published Monday in the Annals of Emergency Medicine, found emergency physicians were more likely to use the drug on heart attack patients, who have a 1 percent risk of brain hemorrhage.

It’s also called the "Walk or Die" therapy, as some of those treated can get a lot better or very very much worse. I don’t know any ER doc who is happy about the whole ‘TPA for CVA’ idea. There was a big push to TPA strokes after the first study (by NINDS, done by the NIH). To the best of my knowledge, there have been studies that tried to replicate the NINDS results, and none have been able to get the same good outcome ratio of the original study.

This application for TPA crosses my ‘First Do No Harm’ line. It’s a drug that may have an (unpredictable) upside, but has a huge downside in stroke. To me, the definitive study of who, and when (and where) for TPA in stroke has yet to be done.

I’m surprised you didn’t get some comments on this already. TPA for strokes is in my opinion a massive boondoggle. I wouldn’t even call it “walk or die”, more like “small improvement in function after 2 months of therapy compared to placebo, or die”. Everybody seems to have an anecdote about giving TPA to a stroke patient and having them get better. Well, I have anecdotes about stroke patients getting better without doing anything – they’re called TIA’s.

Even worse, the media picked up on it educating everyone about “brain attack!” and has people thinking all they need to do is go down to the ER and reverse their CVA, even if they’re just having a little tingling in their foot. This was a treatment indication that was for some reason was manufactured and just took off.

I have had several patients (or their families) REQUEST “that clot buster” medicine when they come in with stroke symptoms — Go Big Advertising Budgets, Go.

Their excitment is somewhat tempered when I tell them that the medicine has as good a chance of killing them as making them better. I have never given it, and don’t plan on starting.

Ok, see, I am one of those patients who has been prepared to arrive at the emergency room demanding TPA, for the reason that my own research led me to believe that this was the most reasonable course.

And yes, ?my own research? consists largely of wading through the results of various Google searches ? but it is the best I can do since few doctors (and, in my experience, NO neurologists) will discuss this sort of thing with patients in any meaningful way.

It seems to me that whether or not to administer this drug (absent the definitive studies that may or may not be forthcoming) should be highly dependent on the individual case. In my husband?s family, the men pretty regularly have serious ischemic strokes, which they survive, since they are otherwise vigorous and fit, but survive to spend years severely disabled. If I should ever find my husband in mid-stroke, I think TPA would be a really good gamble. On the other hand, your information makes me think that on that Saturday a few years ago when I experienced a complete inability to understand written language, with no other deficits and no family history, to have given me TPA would have been just as dumb as what my then-physician did, which was to tell me to make an appointment for the following Monday.

At any rate, this is a decision I think that I, as a patient, have a right to participate in. I hope at least that physicians are not aligning themselves as ?for? or ?against? TPA without regard to the variables.

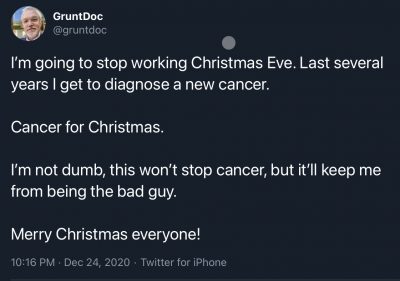

Ditto the above. You get to be the bad guy and explain to the family why their loved one (with symptoms for 6 hours, 6 days or even a week or more) didn’t get the clot buster.

It makes it difficult when EMTs, medics, triage nurses, sometimes even ED techs (and I mean no offense here), who only know about the drug, but not the indications, risks and dangers of the drug, mention it to families.

I think that as ED physicians, it is OUR job to educate our prehospital providers about this aspect of medicine as well. We give educational lectures about teh Cincinnatti Prehospital Stroke Scale, the easiest scale in the world to use, and to get them to the ED as soon as possible, but additional information is frequently NOT included in their curriculum…about the contraindications & risks of fatal hemorrage. We are not beign fair to our prehospital colleagues if we do not give them this education as well.

At our House, we have neurologists on call who are at the hospital within 5 minutes when we call them with a TPA candidate, which we always do. But I’ve only ever seen them give it once, usually they too find ample reasons not to give the drug.

Belinda,

Of course the patient is a participant in the decision. But there is a very narrow set of circumstances that include time since onset, severity of symptoms, recent medical issues/surgery/proceedures that only make a patient a CANDIDATE to consider therapy. Probably 95% or more of patients with stroke symptoms that I see do not even fall within this set of circumstances.

If the patient DOES fall into this very small group, additional neurologic scores may be added up, NIH stroke scale, for example to continue the process of selecting possible patients for inclusion. If the patient does meet all of these narrowly defined criteria, only THEN would the discussion get underway with the patient about whether or not to administer the drug.

It would be malpractice to administer the drug to a patient when the family insists if the patient does not even fall into the category of potential candidates.

While moonlighting in residency, a patient came in and teld me he was having a recurrence of his stroke symptoms, and his doc told him to come to the ED right away “for the stroke drug”, meaning TPA.

His stroke symptom? Numbness in his hand, without any other finding. He wasn’t happy when I told him he wouldn’t be getting it.

I’m really just very interested to know this rather significant “down side” – you are correct that there is a pervasive public perception (which apparently extends to many physicians) that TPA is the end-all, cure-all, thing one must have in the event of a stroke or maybe-stroke.

My favorite doc reminds me that the word comes from the Latin “doctore” – to teach. Y’all have done a bit of that for one trying-to-be-semi-informed patient- thx.

Belinda, you raise very good points. If your husband were having stroke symptoms as you mention above and you and he came to my ER, I am required to tell you about TPA and give you that option (assuming he met criteria to receive it). This is a bit of an ethical problem since I believe TPA is a bad treatment and stands a good chance of killing the patient. Still, it is FDA approved and taught in ACLS courses so I have to tell you about it and give you that option.

In practice though, the percentage of patients who actually meet the guidelines to receive TPA is tiny. Of those that do, the family or patient will almost always ask me what I think they should do, and go with my advice.

It’s just amazing to me that while medications like Vioxx, Rezulin, Redux, etc are removed from the market, TPA not only stays on the market (for treatment of CVA), but is heavily pushed. At least those other meds had some proven benefits to go along with their bad side effects. As someone else pointed out, TPA usage in strokes is all based on one study of about 300 patients that hasn’t been well duplicated.

My final beef with TPA is that in order to expect the kind of results found in the NINDS study, I have to be able to duplicate the study conditions closely. As I have worked mainly in smaller ER’s, I don’t have neuroradiologists and neurologists around most of the time. I would guess most ER docs out in the boonies don’t have the training of the ER docs in the NINDS study either. This raises the possibility that the TPA will be given inappropriately a higher percentage of the time in small ER’s. In my opinion, small ER’s shouldn’t even be thinking about this stuff.

As a neurologist preparing to talk to our ER staff about tPA, I came across your comments and feel compelled to respond.

Although tPA certainly increases the risk of brain hemorrhage (6% vs .6% in original NINDS study), there was actually a slightly lower mortality in patients who received tPA (3 month mortality was 17% in those receiving tPA and 21% in those receiving placebo). What this shows is that stroke carries a high risk of death besides the risk of hemorrhage. There is risk in tPA treatment, but also risk in not treating with it.

A more recent review on the safety of tPA (Archives of Neurology, vol 62, page 362, 2005) includes additional studies since the 1995 NINDS publication, and also confirms no increase in mortality in those receiving tPA within 3 hours of stroke onset.

The benefit of treatment with tPA was that at 3 months after the stroke, 50% of tPA treated patients had minimal or no disability vs only 38% of placebo treated patients. You can look at this as meaning that there was a 30% greater chance of this good outcome, or an absolute 12% greater number of people with this good outcome, but it may be simpler to say that 1 more person out of every 8 patients you give tPA to will be independent at 3 months. (38% of 8 is 3, 50% of 8 is 4)

But a major point is one already made above – most people are not candidates for getting it. The risk of hemorrhage is increased if the time from stroke onset exceeds 3 hours, if the blood pressure is over 185/110, or if a large stroke is apparent on the initial CT. There are other exclusions that I won’t list.

A significant number of brain hemorrhages were in “protocol violations” where these criteria were not strictly followed – it actually may be safer than the above numbers indicate.

The justification for the “stroke alert” and “brain attack” publicity is to get people to come to the hospital in time to be treated within the 3 hour window. But just arriving in this time frame does not mean they should get tPA – they must meet all criteria or the risk will be too great.

Lastly, I agree that it is not appropriate to give a dangerous medication to someone with a mild deficit, such as numbness, or in someone whose stroke is already improving before treatment can be given.

I encourage you to reconsider using it to help your patients who fit the appropriate criteria.