In an effort to get the word out about their new EM Physicians’ blog ( em-blog.com ) Dr Bukata has asked to post here to generate some conversation, and some buzz for their blog.

Dr. Bukata has long been a leading light in EM, and it’s my pleasure to present:

THE SECRET TO UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE – DOCTOR BEHAVIOR

As the debate goes on regarding the Obama initiatives for healthcare reform, the one recurring theme that is heard is – cost. What is universal access to healthcare going to cost and who is going to pay for it? It really is just about money. The fundamental premise is that, if we spend at current rates, it will cost an ungodly amount of money to cover everyone in this country no matter who pays.

Given that we cannot continue to spend at the current rate, yet we want to insure the 40 million people or so who have no insurance (and all of this is supposed to remain budget neutral over time), the logical answer regarding cost must be reducing per capita spending while increasing the number of people covered.

How do we achieve this goal? There is really only one way. The answer is to narrow practice variation. Practice variation between doctors is absolutely huge. The data are compelling. Even small changes in the degree of practice variation have the potential to save hundreds of billions. I refer readers to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Elliott Fisher, et al (360:9, 849, February 26, 2009). The article is entitled Slowing the Growth of Health Care Costs – Lessons from Regional Variation. This short paper gives examples derived from the Dartmouth Atlas on Health (which I have referred to in the past and which is absolutely fascinating reading concerning Medicare practice variation nationally) that make it clear that doctors are major determinants of healthcare costs. We order the tests, we order the drugs, we put people in the hospital and we determine where they go in the hospital and, to the chagrin of hospital administrators, we determine how long they stay.

Using Medicare as an example, at our current rate of spending growth in healthcare it is estimated that Medicare will be in the hole by about $660 billion by 2023. If per capita growth could be decreased from the national average of 3.5% to 2.4% (just a measly 1.1%), Medicare would have a $758 billion surplus. Just a measly 1.1%.

Now for some examples. Per capita inflation-adjusted Medicare spending in Miami over the period 1992 to 2006 grew at a rate of 5% annually. In San Francisco it grew at a rate of 2.4% (2.3% in Salem, Oregon). In Manhattan, the total reimbursement rate for noncapitated Medicare enrollees was $12,114 per patient in 2006. In Minneapolis it was $6,705.

It is noted that three regions of the country (Boston, San Francisco and East Long Island) started out with nearly identical per capita spending but their expenditures grew at markedly different rates – 2.4% in San Francisco, 3% in Boston and 4% in East Long Island. Although these differences appear modest, by 2006 per capita spending in East Long Island was $2,500 more annually than in San Francisco – with East Long Island representing about $1 billion dollars more from this region alone.

Are the patients sicker in East Long Island? Hardly. There is no evidence that health is deteriorating faster in Miami than in Salem. So what’s the difference? People point to “technology” as being one of the biggest sources of costs in American healthcare. But “technology” does not account for these regional differences. Residents of all U.S. regions have access to the same technology and it is implausible that physicians in regions with lower expenditures are consciously denying their patients needed care. In fact, Fisher and colleagues note that the evidence suggests that the quality of care and health outcomes are better in lower spending regions.

So what is the answer? It is physician behavior.

It is how physicians respond to the availability of technology, capital and other resources in the context of the fee-for-service payment system. Physicians in the higher cost areas schedule more visits, order more tests, get more consults and admit more patients to the hospital. Medicine does not fit the supply and demand model of modern day capitalism. Normally when there is lots of competition, prices go down. Not in medicine. In medicine payment remains the same and is not sensitive to supply or demand.

And normally when there are a lot of businesses providing the same service, there are fewer customers per business. Not in medicine. Although doctors may have fewer patients in an area saturated with providers, they don’t necessarily have fewer visits because doctors determine the frequency of revisits and the literature indicates there is huge variability in what they consider the appropriate frequency for revisits when given identical patient scenarios. And do patients shop prices to choose medical providers – no way – it is impossible. Bottom line – medicine is largely immune to the laws of supply and demand and other economic drivers.

So what’s the answer? It is simple, yet hard. Doctors in high cost areas need to learn to practice like doctors in low cost areas. Are doctors in low cost areas beating their chests and bemoaning the inability to care for their patients with the latest technology? Not at all. But doctors in high cost areas are largely clueless to the practice patterns of physicians in low cost areas and are likely to whine if asked to tighten their belts and learn to be more cost-effective. The good thing – mathematically, this will result in only half the doctors in the country complaining as they are prodded to emulate the practices of their more cost-effective cousins.

To accomplish this narrowing in practice variation, doctors will need help (and, particularly, motivation). Payers and policymakers will need to get involved to facilitate and stimulate the information transfer between doctors. Based on research by Foster and colleagues, it’s advised that integrated delivery systems that provide strong support to clinicians and team-based care management offer great promise for improving quality and lowering costs.

Given that most physicians practice within local referral networks around one or more hospitals, it is suggested that they could form local integrated delivery systems with little disruption of their practice. Legal barriers to collaboration would need to be removed by policymakers and incentives to create these systems would drive their formation.

Fundamentally, Medicare would need to move away from a solely volume-based payment system (since doctors are the drivers of their volumes) and other forms of payment would need to be incorporated (such as partial capitation, bundled payments or shared savings). Hospitals and doctors lose money when they improve care in ways that result in fewer admissions, and they lose market share when they don’t keep pace in the local “medical arms race” (does everyone need a 64-slice CT?). In the current system there are no rewards for collaboration, coordination or conservative practice. This must change.

The bottom line – much can be done to save money yet provide patients with high quality, technologically advanced care without rationing (or worse yet having some government “board” telling you what to do). There is so much waste in the current system largely resulting from physician practice variation that the opportunities are huge.

And, should they choose, doctors are in a position to take the lead. The AMA and other physician organizations can initiate (well, that may be asking a lot) and support incentives that will facilitate the needed changes outlined above. Unfortunately, organized medicine (almost an oxymoron) is more often than not reactionary. “What are they (payors) making us do now?” That’s the typical response. What’s needed is for physicians to take the leadership role that their patients expect of them. The status quo is not an option. And if doctors won’t act, the payors will – because ultimately, the payors have the power. That is one rule of economics that does apply even to the practice of medicine.

W. Richard Bukata, MD

I respectfully disagree about markets not working in medicine, but have few arguments with the rest.

What say you?

Are the patients sicker in East Long Island? Hardly. There is no evidence that health is deteriorating faster in Miami than in Salem. So what’s the difference?…

So what is the answer? It is physician behavior.

No. The difference is patient expectations. Patients in East Long Island are more demanding of high technology, extensive testing for definitive diagnoses of self-limited conditions, and perhaps quicker to resort to litigation for any perceived suboptimal outcome than in Minneapolis.

Stuff like this drives me crazy.

Letting bureaucrats “narrow practice variation” will only result in NHS quality medicine. Patients can do it, but only if they are motivated by the most powerful motivator in the market, money.

The most productive single change in the health care payment system would be to remove the government and insurers from between the patients and the providers. I reluctantly agree that this can’t be done all at once, because the insurers, the government, and even the patients will hate and fear any change. I also that it can’t be done piecemeal for the same reason. We will just have to wait until the whole system crashes due to hyper-inflation. Then – I haven’t died from lack of care, I will negotiate with a bootleg provider. Letting the whole system crash is unacceptable? The go back to step one with determination and no mercy for the bureaucrats who are in the way.

The next level of reform is independent of the first. It should be pursued at the same time. It is also possible, because proponents of reform can blame two groups that the public hates, trial lawyers, and politicians.

Health care providers want tort reform even though trial lawyers hate the idea.

At least some insurers would like to sell basic coverage coverage, even though special interest groups of providers lobby the politicians to mandate more and more coverage.

I disagree about increased supply not lowering prices. The Midland/Odessa area has multiple, out of hospital MRI/CT centers. Result? Same day or next day service, and the self pay price has actually gone down.

People with high deductibles or no insurance *do* shop by price.

This brings up an important point. In a world with a vast number of “contract prices” for health care, who should get the lowest price? I submit the following:

Lowest Prices for Service: The pay at time of service patient. Cash, check or plastic for payment. These patients cost the clinic or hospital the least. There are no collection problems, and zero hassle with precert, verification, RQI, and “guidlines”. This means payment for services received. No global fee based on diagnosis. Some form of this exist in areas with more than one hospital for labor and delivery. If you have 9 months to plan, you pick your hospital and physician, and cost will probably be one of the items you consider.

Second Lowest Price: Payment plan. Still no hassle, but no cash up front. No interest, but no more than 20% added to price.

Charity Patients: Same billed fees as the payment plan, but with difference between collections and fees fully tax deductible.

Insurance Plans: These groups are used to contract requirements that they pay the lowest rates of anyone. This is insane. The various insurance plans should *all* be billed at higher rate than self pay patients. The insurance plans need a huge staff for coding, pre-cert, claim follow up. These actions also eat up physician time. It boggles the mind that administrators negotiate discounts with insurance plans, despite the vast increase in work load and *lower* clinic/hospital efficiency. The very lowest fee charged to an insurance carrier should *never* be less than the charity fee. If a physician has to pick up phone to get care authorized, that fee should be *higher*. PPO contract? Fees should rise 2% for each staff person that must be hired to deal with billing and claims issues (less for large hospitals, my background is in a clinic setting).

Note: The pay at time of service patient may have HSA or insurance, but the *patient* pays, and may forward bills to some insurance carrier.

I hate to say it, but he’s only partially right, and wrongly assumes physicians have all the power in this relationship. It’s simply not true for ED docs.

Patient demands drive a huge amount of this, and we ALL know the consequences of failing to meet patient demand/expectations: complaints, pissed-off administrators, contract jeopardy, lower Press-Ganey scores, and litigation. Like it or not, physicians really aren’t “in charge” of medical care; our current system simply has too many “masters” that we have to serve.

In my experience, people want what they want: a CT for their kid’s head bonk, a pregnancy ultrasound., a CT for their abdominal pain, a cardiologist in the ED, an MRI for their neck pain. You can try to talk people out of these things, but honestly, how often does THAT work? And who has time in a busy ED to have the necessarily long conversation required to talk somebody out of something they’ve already decided they need/want?

Don’t put it all on us. Speaking only for myself, I’ve got enough responsibility already.

I essentially agree with NewGuy that many tests are ordered out of a fear of litigation and to meet patient expectations. Unfortunately I don’t see the proposed changes in health care doing anything to change either one of those factors, in fact Democrats are unlikely to address tort reform and Obama is careful to say the government will not come between patients and doctors in decision-making.

There is a third factor though, not so much related to ED docs but more to office and hospital-based docs whose income is tied to procedures and testing. In my town are physicians who obviously are doing a lot more scopes, placing a lot more stents, doing more angiograms and ordering more tests on machines they happen to own as compared to other physicians in town. Similarly there are generalists who refer out at the drop of a hat and order MRIs and labs indiscriminately.

Other than tight HMO-type regulations I don’t see a good way to address that problem. It is very tough to prove a test should not have been ordered, a procedure not performed or a consult not written. Although I hate to discourage private enterprise physicians owning their own CTs, MRIs, nuclear medicine, etc seems to be a recipe for over-utilization.

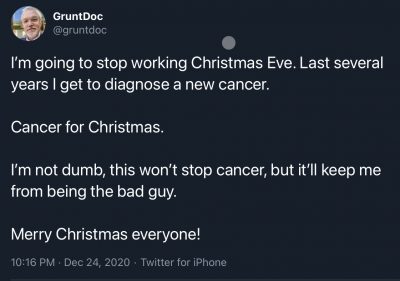

I posted this “tweet” yesterday. Says a lot!

Why Primary Care Doctors are fed up http://bit.ly/6Oj0s

Dr. Kelly Sennholz

Denver Colorado

http://twitter.com/mtnmd

I agree with the group here.

Patients don’t shop for prices because prices are largely hidden and patients don’t know how or where to look.

A substantial portion of this essay relies upon a false premise about supply and demand. The concept of supply and demand only works in a free market. Medicine isn’t a free market.

Make medicine a truly free market and you’ll see how market forces work.

Let the people on Long Island have their 64 slice CT scans. Give them whole body radiation every other week if they want it. Want to see utilization drop like a lead balloon? Start a policy where insurance only covers one CT scan per year – and that’s a measly 16 slice CT. Want the 64 slice? You pay extra. If you’re good, maybe you can carry over one CT scan to following years. That would guarantee 95+% of people on East Long Island would obtain no more than 2 CT scans in any 12 month period.

Even better – prohibit insurance coverage for CT scanning. Then every time a patient goes to the ED with abdominal pain, they’ll ask “Why are you doing that CT scan? Can’t you do something else my insurance will cover?”

It isn’t just a matter of there being “no rewards” for collaboration, coordination or conservative practice. There are several penalties for practicing in such a manner – more time obtaining and reviewing results means less time with patients. When payments are cut every year, the only way to maintain profit is to see more patients. Conservative practice is great until there is a bad outcome. When things go wrong, no one thanks you for saving them money.

He who has the gold makes the rules. To disempower the payors, we have to separate them from the practice of medicine. That ain’t going to happen. Ever.

How about Reimbursing physicians for *not* ordering tests?

You get paid a flat base fee for seeing a patient, possibly based upon chief complaint, and then penalize a small amount for each test, but reward for POSITIVELY diagnostic tests.

Just a thought.

Instead of a patient coming in for a ball of nothing, and getting a huge workup, they get a small, high-yield workup. The physician capable of saving the money gets to pocket a portion of those savings. THAT is how free markets normally work. Tie that together with tort reform, and it might be a good step.

But there is a huge amount of truth in managing expectations. When people com ein basically demanding expensive testing, there are few incentives to not order it.

Doc Russia you are describing things that have already been tried, and often have been criticized as “bribing” doctors not to take adequate care of people. The concept of doctors being rewarded for providing more focused care makes a lot of sense, but has to be somehow balanced by incentives to make sure the doc doesn’t swing too far the other direction and not do appropriate testing.

Goatwhacker speaks the truth. Capitated HMO plans were widely criticized during the 1990s for paying physicians for doing less. It also seems somewhat perverse to pay physicians NOT to care for people, and probably opens physicians up to the kind of criticism generally reserved for the federal government when it pays farmers NOT to grow crops.

I also tend to have the philosophy of doing more than you HAVE to do. I find it makes for more thorough care, and helps you look a bit deeper for the less-common diagnosis. I’m not saying everyone should necessarily practice that way, merely that I practice that way.

That probably makes me, in the immortal words of Michael Douglas, “not economically viable.”

How would anyone know what the true “market” would do? There hasn’t been a true free market in healthcare delivery in decades. When the government provides 50% of the cash, and the bulk of the rest is set based on what the govt. pays, how exactly will we ever see a free market?

You can whine about this reform and that reform that you want, but unless the above changes, the only reform we’re going to get is MORE government.

Point taken.

I was just spitballing.

From a physicians point, it is true that we want to strike a balance between too much testing and too little. The thing is that this is so highly variable. Personally, if I have a good hunch of what is going on based on H&P, I tend to be minimalist in testing. As diagnostic uncertainty rises, I test more. If I get a horrible historian with an equivocal exam, then I always end up doing more testing. Most of it turns out to be unnecessary, but what is the other viable option?

You’re right. Veterinary workups are always expensive… because what we cannot get in H&P, we compensate for with testing. It’s also not all defensive (though some of it is), there is good science behind much of it; severe head injuries and septic patients often can’t talk to you, but being minimalist will kill those patients.

We’re going to be second-guessed after-the-fact anyway… and I personally like delivering a thorough workup. If the FedGov thinks it’s going to financially restrict me to minimalist workups, while simultaneously forcing me to shoulder the increased liability for that action, they can get f*cked.

And I mean that quite sincerely… f*ck them right in the ear. Don’t tie my hands and then beg off by saying “we don’t make the medical decisions… the DOCTOR does…” (because you KNOW they’ll say precisely that) when angry patients and their attorneys start circling.